I don’t know why but I am always fascinated in old packaging & wrapping techniques. Maybe its because these are hard to come by now. We have few surviving examples and some are just lost forever. Then too just like psychology goes into how we package things today to market and sell an item I find it interesting to see the psychology behind this from times long gone. And of course I love paper craft! So when I find articles about these subjects I am always reading with interest. And what can be more fun than talking about butter and cheese boxes? Oh and be sure to check the links for fun after the article…one of them includes a printable antique butter box.

Packages Made of Paper

THERE arrived on the New York market the other day a lot of oranges from one of the smaller West Indian islands that used to ship fruit regularly years ago, before Florida and California developed their citrus industries. It was high-class stuff, with the heavy juice content and delicate flavor characteristic of citrus grown in the tropics, and it came in good condition, with little decay.

Yet buyers were found with considerable difficulty, and the price realized was not in keeping with its real merit, because packing had been done in big wooden boxes of a Spanish style long ago discarded here. Buyers didn’t know how to figure on the unusual quantities and counts, and were apprehensive about passing them along through the trade.

Packages became important with the need for more skillful marketing of soil products. Some of the most successful developments in marketing have been organized round improved packages, such as the Western box for apples and the Georgia carrier for tender fruit and fancy winter vegetables.

The first improvements made in packages were with those used by the trade–boxes, baskets, crates and hampers adapted to the produce dealer and grocer, seldom seen by the consumer. This type of package was almost invariably made of wood or wood veneer.

By and by the new movement for better marketing began to reach the consumer. Growers undertook to send family shipments of fancy stuff direct to housewives by parcel post and express, and also to pack family quantities to be sold through grocers. This called for a new type of package, one of much smaller size than the wooden box or crate, more attractive to the eye, because it was seen by consumers used to attractive containers for other food articles, and with features making for cleanliness and sanitation, in keeping with the general food development. Such packages were nearly always made of paper or paper fiber in some form.

Much Pioneering to be Done

During the past year or two there has been a vigorous development of these paper packages. Each month sees some novelty introduced, and it is likely that this activity marks the beginning of widespread changes in packing and marketing. Some of the leading types have therefore been collected for description.

The grower will do well to bear in mind, however, that these paper consumer packages are entirely distinct from the wooden and veneer trade packages, and that at this particular stage of development it is sometimes risky to try switching from one to the other.

Some day the produce trade may handle wholesale quantities packed in consumer units– that is, paper containers holding small, sealed lots for the housewife, Cheap, Strong, Throw-Away Containers for the Consumer marketed through the trade in wooden crates. That is the tendency in all other foods. But just now the produce trade would find such packing as perplexing as it found the old-time Spanish orange box.

Much pioneering remains to be done. Everybody needs to be educated over a period of years. For the individual grower a safe motto is “Let George do it.” But when the grower ships fancy products direct to a list of parcel-post customers, or delivers milk over a route, or has worked up a business with grocers in near-by territory, the paper consumer packages offer real market advantages.

The whole situation is clearly illustrated by the paper milk bottle.

Glass milk bottles were a wonderful improvement in dairy marketing in their day, and are now so thoroughly standard that most people have forgotten the difficulties under which they were introduced. Producers had to install machinery for filling and capping them, and the public had to learn to pay higher prices for cleaner milk. Nobody would want to go back to the old milk can and dipper now.

Glass bottles have disadvantages that paper bottles overcome. The glass container is used over and over, and so falls under suspicion of uncleanliness. Nobody knows whose household it was in last, and it is a fact that thousands of milk bottles are recovered from the waste dumps in big cities, to be put back into circulation. The glass bottle is made rather expensive by its short life; it is estimated that it is used less than a dozen times, and then is lost or broken.

The new paper milk bottles are made to be used once, and then are thrown away or destroyed by the consumer. This is a sanitary advantage so great that it would seem as though they would be adopted immediately, without hesitation. But they have disadvantages that must be overcome gradually.

Cost is one. A quart paper bottle of good type costs about one cent and a quarter, against about four cents for a glass quart bottle. But on the basis of use twelve times, the glass bottle costs only one-third of a cent a delivery against one and a quarter cents for the paper container. On a staple commodity like milk that is a price increase which only the best class of consumers are willing to pay at present.

Special filling machinery is required for paper bottles, but up to the present time hardly any such machinery is being built.

The paper bottle also lacks one tremendous attraction of glass in that it is not transparent. The average housewife judges quality of milk by the rough-and-ready method of glancing at the depth of the cream on top of the bottle when she lifts it from the doormat, and when the dealer uses the opaque paper container she has to take the cream line on faith.

The paper milk bottle is slowly and surely coming into its own, however. Manufacturers say that the cream-line objection does not last long when the containers are actually introduced. Nor is the additional cost a serious objection. The idea of once-used sanitary packages is so familiar in other foods that it is only a question of time when the paper container will be generally used for milk.

It is already being used by millions in the dairy industry, and manufacturers say that they have difficulty in keeping up with the demand. But it is entering by the side door, so to speak, instead of the big front door at which the milk is left.

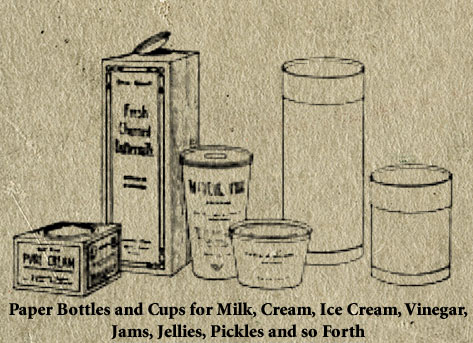

Paper packages are now beginning to be standard for dairy products of higher value and better profit than milk, such as heavy cream, ice cream, cottage cheese, and so forth, as well as jams, jellies, fruit butters, vinegar, cream cheese, butter and other farm products. Thus the idea is becoming familiar to the consumer, and gradually is being extended to milk itself.

Transparency as a Selling Factor

One style of paper container is the cup shape, tapering from the bottom so it can be nested for shipment. This is made of heavy fiber board, thoroughly paraffined to make it waterproof, with a pasteboard cover that snaps into place like a milk-bottle cap. It is creamy white in color, clean-looking, can be printed with any label or advertising matter desired, and is decidedly sturdy. It comes in six or eight sizes, ranging from an eighth of a pint, for individual portions of cream, up to the quart size.

For cheese, jam, and the like, it is made in a tub shape, up to two pounds’ capacity. This style of paper package is now being widely used for jellies, jams and fruit products, largely because its shape resembles that of the jelly tumbler. About the only drawback it has for this purpose is lack of transparency. The color of jams and jellies seen through glass is a prime factor in selling. But some large manufacturers now pack fruit products in paper containers, and the paper package has the advantage of being cheaper than glass for that purpose.

Another style of paper container for milk is the oblong bottle with a friction cap cover that presses tightly into a small round hole in the top, somewhat like a shallow cork in a bottle. This is made of thin, tough fiber board, heavily paraffined, and its sturdiness shown in the fact that one of the very first uses found for it was in the bottling of small quantities of vinegar to sell at ten cents.

Such packages cannot be shipped nested like the paper cup, but when large quantities are used by a big dairyman or milk distributor the manufacturers ship them flat, and the user shapes them up and treats them with paraffin by simple methods. They are made in sizes from half a pint to a quart, and in styles with wide and narrow mouths. The cap can be sealed on with paraffin, making it leakproof and keeping contents intact. It is said that freezing will not cause it to soften, leak or expose contents.

This package is being used for ice cream, certified milk, cream,buttermilk,syrup, honey, pickles and almost every farm product that can be packed in a bottle or can, as well as olives, oysters and grocery staples.

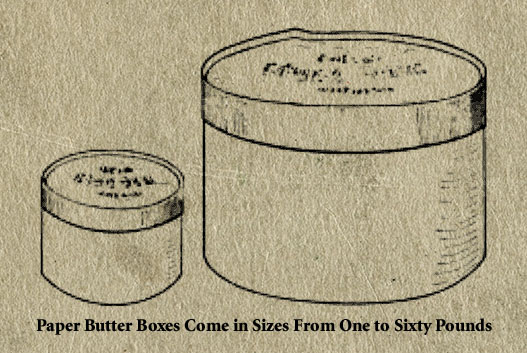

The paper butter tub and cheese box, made of strong, waterproof fiber board, is being used by creameries and cheese factories for large shipments, and by growers who cater to grocers round home. These packages are made in sizes to carry from one to twenty pounds of butter, round like the wooden tub or crock, and of one piece, without seams. Parchment paper lining gives further protection to contents, and they are not only cheap but can be printed with labels and advertising matter.

The paper butter tub and cheese box, made of strong, waterproof fiber board, is being used by creameries and cheese factories for large shipments, and by growers who cater to grocers round home. These packages are made in sizes to carry from one to twenty pounds of butter, round like the wooden tub or crock, and of one piece, without seams. Parchment paper lining gives further protection to contents, and they are not only cheap but can be printed with labels and advertising matter.

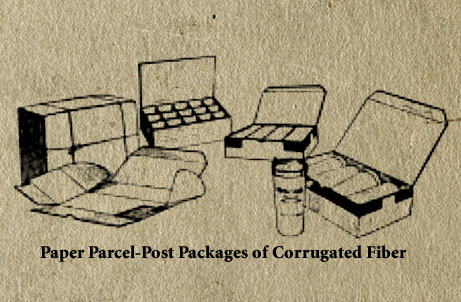

One of the biggest fields of development in paper packages has been among those made of corrugated fiber board. This is the material with a fluted sheet of Manila paper glued between two sheets of plain pasteboard, now familiar everywhere and known for its ability to withstand considerable knocking about, as well as to protect things against heat and cold, the air spaces providing insulation as well as a cushion.

It began to gain a foothold some years ago as a substitute for wooden boxes in general merchandise shipments, being cheaper and lighter than wood. When farmers started parcel-post trade to the consumer, manufacturers followed closely, designing cheap, strong, ingenious packages of corrugated fiber for each kind of shipment.

It began to gain a foothold some years ago as a substitute for wooden boxes in general merchandise shipments, being cheaper and lighter than wood. When farmers started parcel-post trade to the consumer, manufacturers followed closely, designing cheap, strong, ingenious packages of corrugated fiber for each kind of shipment.

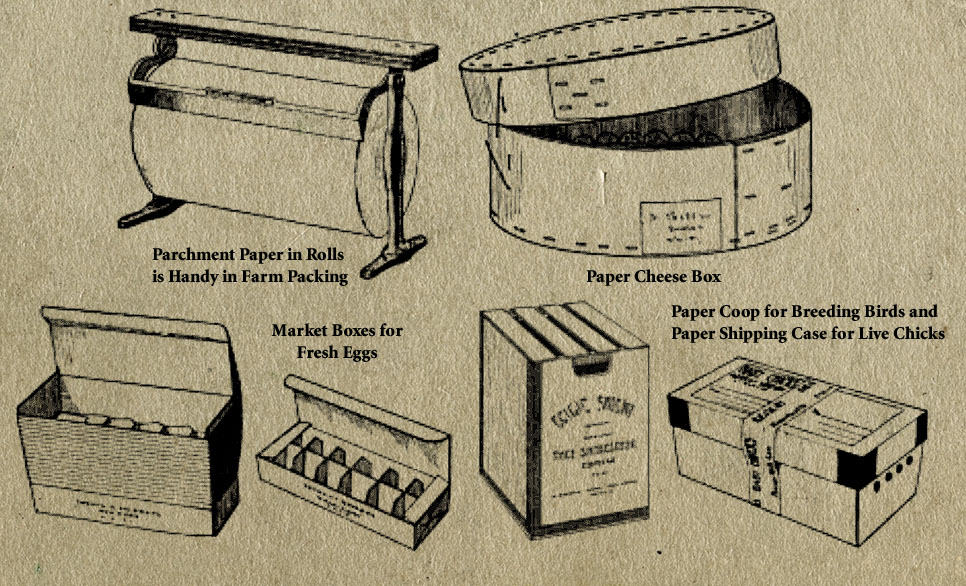

They solved the problem of small egg shipments through the mails, making boxes so sturdy that they could be filled with eggs and dropped several stories without damage. At the same time, these packages were light and cheap. Egg boxes are now made to hold from one to six dozen.

Another early idea in direct selling was the home hamper of vegetables and fruit, sent originally in a wooden Georgia carrier. This has been duplicated in fiber with boxes of half-bushel capacity. Celery, asparagus, mushrooms, fruit, butter, poultry and squabs, meats and country sausage can now be shipped in paper packages cut to fit, ready to use with simple folding; strong, cheap and clean.

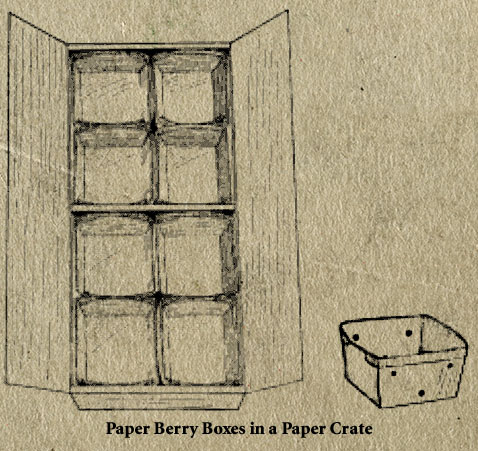

Berries go in a package that incloses the regular berry box of wood or paper; cottage cheese is packed in paper cups and then in corrugated fiber; live chicks are sent in special ventilated boxes for the day-old-chick trade; adult birds, rabbits and other breeding stock go in paper coops, and so on. There are paper packages for jellies and preserves in glass, for hatching eggs, seedling plants, cut flowers and almost everything that is apt to be shipped from the farm.

Berries go in a package that incloses the regular berry box of wood or paper; cottage cheese is packed in paper cups and then in corrugated fiber; live chicks are sent in special ventilated boxes for the day-old-chick trade; adult birds, rabbits and other breeding stock go in paper coops, and so on. There are paper packages for jellies and preserves in glass, for hatching eggs, seedling plants, cut flowers and almost everything that is apt to be shipped from the farm.

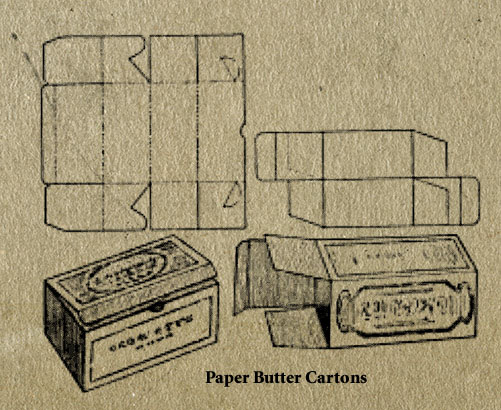

Another widely used group of paper packages, many of them firmly established in the trade, is that of the butter and egg cartons made of light pasteboard, paraffined. These are too frail for shipping by parcel post, and are market packages pure and simple. They offer an attractive container at far less than the cost of corrugated fiber, and may be printed to better advantage.

There is nothing handier, cleaner, cheaper or more attractive for farm packing than good quality parchment paper. This material now comes in almost any size and shape likely to be needed for any purpose. The inside of a butter tub is quickly lined with pieces ready cut to fit bottom, sides and top of tubs from ten to sixty pounds. Brick butter has a similar assortment of sizes and shapes, and the material can also be bought in rolls ranging in width from six inches to three feet, and in liners for barrels and boxes.

The merits of parchment paper are many. It is waterproof, and so prevents evaporation and loss of weight in butter and other moist products. It is very tough, and stronger wet than dry. It is odorless and a protection against odors. It keeps any article clean and secure against contamination, and may be printed with almost any matter desired, in one or more colors.

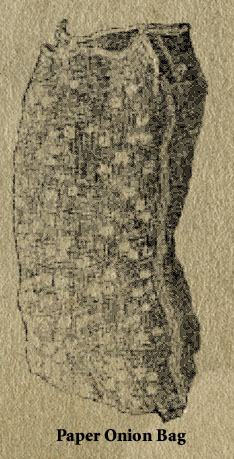

Paper is also furnishing a substitute for bagging. Up in the big onion-growing section of Massachusetts a produce dealer learned about this substitute for burlap, and began experiments with a paper onion sack. Onions packed in burlap bags are often spoiled by heating and sprouting. No matter how widely the meshes are woven, burlap has a tendency to close up.

Paper is also furnishing a substitute for bagging. Up in the big onion-growing section of Massachusetts a produce dealer learned about this substitute for burlap, and began experiments with a paper onion sack. Onions packed in burlap bags are often spoiled by heating and sprouting. No matter how widely the meshes are woven, burlap has a tendency to close up.

It was found that the paper bags, owing to the nature of the material, would preserve an open mesh with rough handling, giving ample ventilation and keeping onions in fine shape. Moreover, these paper bags were strong enough, and could be used several times, because they do not easily soil. The paper onion bag was taken up so quickly that more than a million were sold in one season, and they are now familiar in most produce markets. As this package is made of a long paper fiber that comes principally from Sweden, and supplies have been difficult to obtain during the war, the new onion bag is not being made just now. But manufacture will be resumed as soon as the proper material is available once more.

Paper burlap has also been used with marked success as a covering for cotton bales, and promises to come into use for baling wool, along with paper twine for tying wool fleeces. Burlap is detrimental to both cotton and wool. It introduces foreign fibers into these products which must later be removed at the textile mills at considerable expense, and so reduces the price paid. Quite a little cotton and wool cling to burlap coverings, and cannot be profitably separated, whereas the paper coverings are smooth, and neither cotton nor wool will adhere to them. It has also been found that paper coverings are far less inflammable than burlap, which is a decided advantage.

When used for packing onions, cotton, wool and other farm products this paper material is not so economical as burlap. In fact it costs more than twice as much. As a special package for peculiar conditions, however, it is worth the price, and today there are several mills in the United States developing these products. – Original article Written By John Mappelbeck For Country Gentleman 1916

A couple of fun links from around the web for you –

Here you can print out your own antique butter box:

http://knickoftime.net/2013/01/printable-antique-butter-box.html

If you have little ones or are just young at heart here is a Play Store printable from the 1930s:

https://picasaweb.google.com/113630803541426992026/LetsPlayStore1933?noredirect=1#