One of my favorite things to do is read articles from old magazines and periodicals. I find it intriguing to get a 19th century view on things, including their own recollections of their past. I was searching for articles about school houses since I had read some rather inspiring verses of prose so that I wanted to explore that theme a little more. While searching I ran across a rather unusual article that I couldn’t resist pondering over. It dealt with a very uncommon subject – that of the secret languages of children.

Have you ever have stumbled upon an old journal, book or letter that has some strange markings or gibberish like words in it? I don’t believe I have ever had the pleasure of laying eyes on some secret codes written out with the keys silently lying in the graves of yester-year. But if you have ever used Pig Latin then you will understand what this article was speaking about.

Why Is It Called Pig Latin?

My husband and I indulge in using Pig Latin when we have conversations that we don’t want our seven year old to pick up on. However, we never have stopped to think of why we have this silly little sub-language, or even where it came from. So it was very interesting to find the following information.

The Century; a popular quarterly, published the above mentioned article on the Secret Languages of Children, in 1892. This is what it had to say about the languages like Pig Latin: “It can never be known whether these languages originated in the very first cases with children. The names would in many instances imply that children had to do with them, as they show things familiar to the child and loved by him. So in the secret languages we find animals playing an important part in the naming. The hog, dog, goose, pigeon, pig, fly, cat, and other animals, are attached to these languages. The child in the old-fashioned school, where all sat together, hearing the (to him) senseless and unknown Latin, would naturally attach the name to his language, and thus give birth to Hog Latin, Goose Latin, etc. Seeing or hearing a language, one letter may strike the child’s fancy, as in one the letter h is “hash,” and so Hash language is the result. In another ‘bub’ (b) finds the funny spot in child nature, and so Bub talk comes forth. The child in former days, so frequently hearing of the a-b-c’s, would, upon the construction of an alphabetic language, at once recur to such, and so name this the A-Bub-Cin-Dud language.”

Different Classes of Secret Languages

The author of the article breaks down these secret languages into a few different classes, though he brings to our attention that there are many varieties. I believe Pig Latin would fall into the first category of syllabic. That is described as follows: “The most numerous class–the syllabic–add or prefix a syllable to a word, or insert it between syllables or letters in a word. This form is the most common, and the syllable most in use is gery, with variants of gry, gary, gree, geree, as, Wigery yougery gogery wigery ‘megery? Next in use is vus, with the variants vers, yes, and vis, as, Willvus youvus govus withvus mevus?”

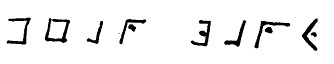

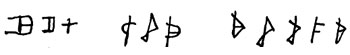

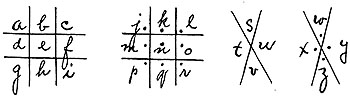

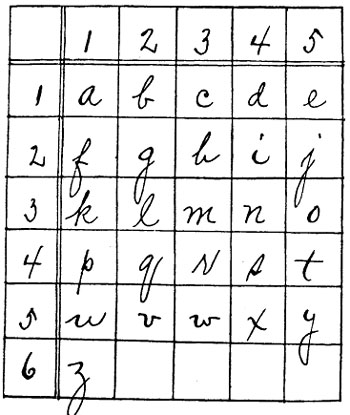

Next up is the alphabetic class. “In the second class–the alphabetic–a very common alphabet is made by placing a short u between a consonant repeated, letting the vowels stand as they are; thus, b is bub, c is cuc, etc. Cipher alphabets are common. Many are arbitrary, being made up by the children using them, while others have been early formed, and used in several generations. One cipher sentence is given so:

‘Are you going?’

An alphabet often met with is made thus:

A sentence is thus:

![]()

‘I am very tired.’

Another cipher alphabet is formed in this most ingenious way:

42.54 42.44 11 43.42.31.51 41.11.55

‘It is a nice day.’ ”

Now the third class is called sign langauge. It is the secret gestures of the hands which when correctly interpretted would relay the secret message. These signs were often procured with the hands under the desk in which other children could see and understand leaving the teacher baffled. The article then asks, “Is there a boy living who has not again and again used the two fingers, pointing upward, to signal to a boy at a distance to go swimming?” Sounds a little like todays “thumbs up”.

Under this same class is also the “Morse telegraphic characters”. The children became adept at reading, writing and tapping these out.

Moving on we have the Vocabulary class. The article mentioned there are few forms of this class of language. Some are just contributors of of when being very young and learning the english language. What we would call baby words, like ba-ba for bottle, ect. But others are just made-up non-sense words. A few collected from children when the article was written are :

TUELO-TUELO. A jay-bird.

TRAMP-TRAMP. A man.

TIP-TIP. A lady.

PAT-PAT. A child.

WAH-WAH. A crying baby.

GOO-GOO. A good baby.

The following are from a paper containing twenty-five such, found by a lady among her childhood savings:

FOOL DEEL. I will kiss you.

SQUIGGLE. Yes.

Mossy BANKS. I will go to supper with you.

SEAL. Oh, dear me!.

The fifth class is that of the reversing of letters of the words and even the whole sentence. I am sure most of us are familiar with this type code. Certainly an easy remedy – just put it to a mirror.

Then of course there are some forms of these secret languages which have no class in which to fit into. The article mentions a few of these.

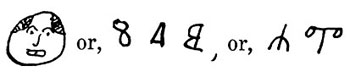

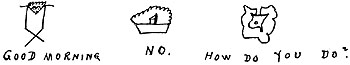

“In one such a slip of paper is prepared by cutting holes in it which fit over certain words on certain pages of a book, and thus make sentences. Another comes from that slip of paper mentioned as found among childhood’s remains. On this paper are thirteen such characters as these three: “

Then the article mentions at length what it considers as the most remarkable of them, which was deemed the “Berkshire Gabble”. This language was comprised by two young ladies around 18 years old. They devised as system of naming feelings that the English language just didn’t have words to describe.

“For instance, one day, when these two girls and one other were together, they decided to make a word for ‘the feeling you have in the dark when you are sure you are going to bump into something.’ One shouted, ‘I choose first syllable ‘; another, ‘I choose second ‘; and the remaining child had to take the last one. Each thought to herself a syllable, and when all were ready they fitted them together in the order chosen; the result was ku-or-bie–kuorbie. If the word sounded to them like the sensation, they left it as it was; if it did not, they changed it.”

They even made a dictionary of their “feeling” words and the article lists some of them.

” … the class of city girls who, when they go to the country in the summer, sit on the piazza, dressed up in fine clothes, doing fancy work; who can’t climb, won’t run, and are afraid of cows. The word at first was raggadishy, but finally became rishdagy. They approved of the latter because in order to pronounce it they had to turn up their noses in reality, which mentally they always did at such people.

Another word of some picturesqueness is pippadolify, which means young men who wear very stiff collars, newly laundried duck trousers, and walk as though afraid of creasing them or soiling their shoes.

Trando. The thing which first suggested it was a gate on a hilltop, sharply outlined against the sky. Beyond it they could see nothing except the blue heavens, stretching on, on, forever. But because there was a path to the gate, and paths always lead somewhere, there must be something beyond. What that something was no one could tell without seeing it. To the imagination it contained as many possibilities as the future. This feeling of the semi-transparency of vastness they called trando.

There was one thing that troubled one of these children very much: Where did utterly lost things go, such as the water which vanishes from a mud puddle or the cloth which gradually disappears from the elbows of dresses? There must be some place apart from the earth for such things; so she made up a name for it–Bomattle. The idea of the place gradually grew. She realized that some of the things which went there came back, as the water came back to the puddle in the form of rain. It came to embrace larger things as the child grew, and she has never outgrown it.

ANKERDUDDLE, adj. Weird and spectral and romantic feeling of a big, solitary house by moonlight.

BOGEWATSUS, adj. Fluttering, though determined, feeling before a high jump or dive (as in bathing).

BOZZOISH, adj. A person lacking individuality in his looks.

BUTTOR, adj. Peaceful summer Sunday morning feeling out of doors, with the hum of bees and the fluttering of butterflies.

CLONUX, adj. Grown up for one’s age.

CREAMY, adj. Desire to squeeze a little fat cat or baby.

DINX, adj. Vulgar and “showy off.”

DOVEY, adj. When one seems to resemble one’s name. This last is very hard to explain, as many of them are–especially in good English.

EVO, adj. Instinctive feeling that some one whom you do not see is in the room with you.

FAXSY, adj., is one of our best and most used words, and explained in our dictionary as “stuffy-parlorish,” which means a close little country parlor, its water-lilies under glass domes, its dried pampas-grass in tall vases at each end of the mantelpiece, its shell and seaweed designs, its parlor organ, etc.

FOMO, adj. Nervousness about squeaking slate pencils, etc.

GOATY, adj. The kind of person who uses long words to express very ordinary emotions.

HALALA, adj. Exultant feeling, wild and inspiring, from the influence of being out in a wild wind-storm by the sea, etc.

HAMALET, adj. The indulgent cheeriness of mothers.

HAWPLOW, adj. Sinking feeling, as in a marsh.

HEELY, ad]. Feeling of some one close behind you in the dark.

KUAWBEE, adj. Feeling, with one’s eyes shut, as if running into something.

LULLISH, adj. Feeling, in going up or down stairs, that there is one more step (thinking there is, and taking it).

MONIA, adj. Presentiment that something is about to happen.

MOUSY, adj. Applied to your unfortunate companion who is not wanted, is in the way, and is staying in the hope of getting something by it.

MUNCHY, adj. Up-to-date in every way–dress, speech, manners, and ideas; that is, up-to-date in a worldly way rather than intellectually.

NOTTLE, adj. The kind of practical children who play dolls and “horse,” etc., as a matter of course.

OPPLE, adj. Crackly and glimmering, as sheets of bright tin or copper.

OWLY, ad]. Feeling one has when one has found anything.

PALDY, adj. Feeling of the world being like a theater.

PATBOORAY, proper n., was the name of a club about six of us had for anti-slang-using.

PILTIS, adj. Feeling when one has made something all alone, or bought something with one’s own money.

PUSSY, adj. A child capable of making up funny faces.

QUONO, adj. Feeling of delicious sense of perfect rest — drowsy and luxurious.

REWISH, adj. Feeling numberless eyes on you as you are about to recite something, etc.

SABBA, adj. Individual house smell.

SPAILY, ad]. Old-fashioned and awkward– I may almost say directly the reverse of “munchy.”

STOWISH (or SToIsH), adj., is one of our best, but one I really cannot possibly explain. Out of a large number of persons or things, there is always one that is stowish–and, considering all points, is the one least conspicuous. We used to differ as to what was stowish. It is a word which is wholly comparative, wholly relative. One thing alone can never be stowish; i. e., from the alphabet, d, k, n, and t are considered most universally among us as most stowish. Thursday was the most “stowish” day in the week, and April and November of the months. This is very vague, but the best I can do.

THUKS. An unexplainable sensation about an old blue pump.

VANIDIES, n. The “sillies.”

WILLISH, ad]. When a thing smells as something tastes (or taste reminding one of smell).

ZONCE, n. Terrible hatred.

ZUMMY, adj. A closely knit, neatly built, shorthaired dog.”

So when thumbing through old school books, diaries, scrapbooks or perhaps even letters and notes, and you happen across something that’s seems coded or gibberish perhaps it was just a child’s sub-language to connect to its peers. And next time you use Pig Latin, you can be assured you are following your ancestors of old who also found secret languages fun to use with their friends and acquaintances.

“…we have a great fact here which must be accepted and acted upon– the great inventiveness, acquisitiveness, patience, and language-forming ability of children at this secret-language period.”