This article was found in The Manufacturer and Builder – February 1870 issue. It looks at how fish hooks were still being produced in the 1870s and near the end of the article it briefly compares to how they were made many years before this.

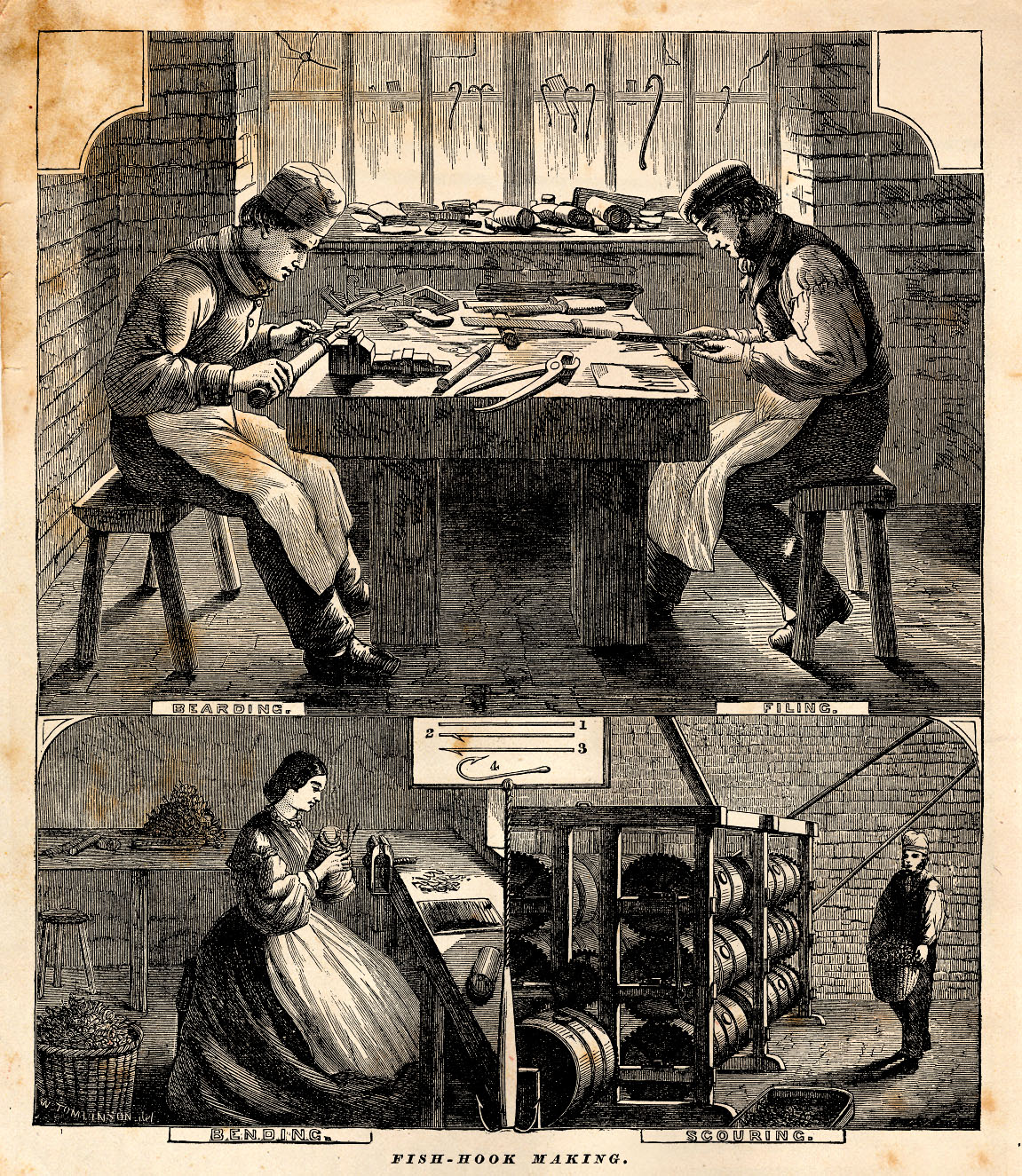

The wire for making fish-hooks is procured in coils from Sheffield or Birmingham, of different qualities, varying with the kind of goods required. All first- class hooks are made from the very best cast-steel wire; other qualities are made of steel, but inferior; while the common sorts of large hooks are made of iron. Cutting the wire into lengths suitable for the hook about to be made is the first operation, and is performed in two ways. The small and medium sizes are cut from the bundle or coil in quantities, between the blades of a pair of large upright shears, in the same manner as needle wires are cut; but large sea-hooks made from thick wire are cut singly, each length being placed separately upon a chisel fixed in a block or bench and struck with a hammer. What are called “dubbed” hooks are “rubbed” after being cut – that is, placed in a couple of iron rings, then made red-hot and rubbed backward and forward with an iron bar until the friction has made every wire straight. Hooks in general are not rubbed, but are at once taken to be “bearded”, or barbed, which is thus performed: the bearder, sitting at a work-bench in a good light, (see engraving,) takes up three or four wires with his left hand between the finger and thumb, and places the ends upon a piece of iron somewhat like a very small anvil, fixed in the bench before him. In his right hand he holds the long handle of a knife of peculiar shape, the blade of which, having the edge turned from him, is placed flat upon the wires, the knife-point at the same time being passed under a bent piece of iron firmly fixed, which enables him to obtain sufficient leverage to cut the soft wires and raise the barb, or “beard”, this being done by pushing the handle forward, while the point remains fixed, as described. It becomes a laborious operation in the case of very large sizes, requiring not merely a forward motion of the arm, but a strong push with the body against the handle.

They are next taken by the filer, who makes the points. Each barbed wire is taken up separately, fixed in small pliers held by the left hand, then placed upon the end of a slip of boxwood and filed to the degree of sharpness required. This is a matter of great nicety and delicacy. Common hooks are pointel with one file, but the finer sorts require two or three fiat and half-round. Large sea-hooks have the ends flattened, and the burr cut off on each side with a sharp chisel into a roughly-shaped point, previous to being filed. The points of “dubbed” hooks are not filed, but ground upon a revolving stone, and this process is called “dubbing”. When the points are made, the “benders” proceed to operate upon them. The woman seen in our illustration holds in her left hand a piece of wood, at the upper end of which is inserted a curve, or “bend”, of steel projecting slightly. Taking a wire in her right hand, she catches the beard upon one end of the steel curve and pulls the wire round into the proper “hook” shape. For the larger sizes the “bends” are fixed, not held in the hand.

Nothing now is necessary to perfect the formation but “shanking”, which is done in various ways. Hooks are flattened at the shank end by a workman who holds the curved part in his left hand, rests the end upon the edge of a steel anvil and strikes it one sharp blow with a hammer. Some are tapered at the end with a file, while others are simply curled round, or “bowed” to provide a fastening for the line. With steel hooks, hardening is the next process; but iron ones require converting, or “pieing” before they will harden. The pie-hole is a recess with a large, open chimney, and in this recess is placed an iron pot filled with alternate layers of hooks and bone-dust. At a little distance from the pot bricks are built up all round and the space filled with coal, which, when lighted, creates an intense heat, and to its action the hooks are exposed for about ten or twelve hours, allowed afterward to cool, and are then fit for hardening. To effect this they are exposed to a great heat upon pans in a fire-hole, and while red-hot poured into a caidron of oil. Small hooks are afterward tempered in a kind of frying-pan, partly filled with drift-sand and placed over a fire. The larger ones are tempered in a closed oven at a low heat.

When these operations are completed, they are taken to the scouring-mill, of which we have given an illustration. It is occupied by a number of revolving barrels driven by steam-power, and containing water and soft-soap, into which the hooks are put and allowed to remain for two or three days. At the end of that time, the friction having worn them all bright, they are taken out and dried in another revolving barrel contaiaining saw-dust. Bluing, japanning, or tinning follows, of which the two latter are performed in the ordinary way, and the bluing is done by exposing them to a certain degree of heat in drift-sand over a fire, in the same way as small hooks are tempered. Counting, papering, labeling, and packing complete the series, and the goods are then ready for the market.

Readers of the foregoing description can hardly fail to notice the extreme simplicity of most or all of the processes; and it seems strange that in such an age as ours there should be little improvement in the mode of production, as compared with the fireside practice of amateurs two hundred years ago. In the Secrets of Angling [ I believe this is a repirnt of the book this is speaking of. ] a very rare and curious book, the author describes the making of hooks (as practiced by himself) in the following terms: ” Soften your needles in an hot fire in a chafer. The instruments – First, an hold-fast. Secondly, an hammer to flat the piece for the beard. Thirdly, a file to make the beard and sharpen the point. Fourthly, a bender, namely, a pin bended, put in the end of a stick, an handful long. When they are made, lap them in the end of a wire, and heat them againe, and temper them in oyle or butter.”